Judge Koh: Rip Up All the Qualcomm Licenses

U.S. District Judge Lucy Koh of the Northern District of California has handed a sweeping win to the FTC in its antitrust case against Qualcomm, calling out the wireless giant's lawyer-executives as the "architects, implementers, and enforcers" of anti-competitive practices.

May 22, 2019 at 08:33 AM

6 minute read

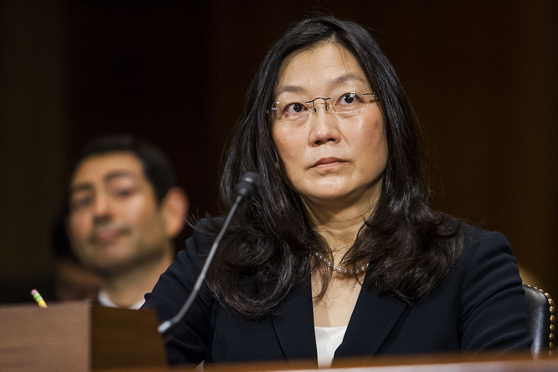

Judge Lucy Koh, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California (Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM)

Judge Lucy Koh, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California (Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM)

U.S. District Judge Lucy Koh of the Northern District of California has just brought a world of pain on Qualcomm Inc.

Koh threw the antitrust book at the San Diego chipmaker Tuesday night, finding in a 233-page order that Qualcomm illegally monopolized markets for the CDMA and 4G LTE modem chips used in premium smartphones.

The judge gave the Federal Trade Commission almost everything it wanted, ordering Qualcomm to stop threatening to cut off chip supplies to smartphone manufacturers who balk at its licensing terms—also known as Qualcomm's “no license, no chips” policy—and to renegotiate existing license agreements free of that threat.

“It makes little sense for the court, having found that Qualcomm's patent licenses are the product of anti-competitive conduct, to leave those licenses in place,” Koh wrote. “To permit Qualcomm to continue to charge unreasonably high royalty rates would perpetuate its artificial surcharge on rivals' chips, which harms rivals, [manufacturers], and consumers, and would enable Qualcomm to continue to reap the fruits of its Sherman Act violation.”

She further ordered Qualcomm to make its standard-essential patents available to rival chip suppliers—not just handset makers, or OEMs—on fair, reasonable and nondiscriminatory (FRAND) terms. And she instructed Qualcomm to stop entering into express “or de facto” exclusive dealing agreements or to interfere with any customer from communicating with government agencies about potential regulatory matters. Koh found that Qualcomm struck a $100 million deal with Samung last year, for example, “to extinguish Samsung's antitrust claims and to silence Samsung.”

Koh's findings of fact and conclusions of law culminate a bench trial held earlier this year in Federal Trade Commission v. Qualcomm. The judge found Qualcomm's witnesses gave “pretextual” testimony that was not credible when compared with internal documents and statements Qualcomm executives made to the Internal Revenue Service.

She called out Qualcomm lawyers for especially harsh blame. “Lawyers—including Derek Aberle, Steve Altman, Eric Reifschneider, Fabian Gonell, and Lou Lupin—were the architect, implementers, and enforcers of Qualcomm's licensing practices,” she wrote.

“Lawyers explicitly stated that Qualcomm's licensing practices raised concerns about antitrust liability, but chose to continue those practices anyway, with full knowledge that Qualcomm's unreasonably high royalty rates violate FRAND and that Qualcomm's licensing practices harm rivals. That willful, conscious decision to continue Qualcomm's licensing practices is further evidence of intent to harm competition.”

Aberle and Altman are former Qualcomm presidents. Reifschneider is a former general manager. Gonell is the current senior vice president for licensing strategy. Lupin is a former general counsel.

Koh also found that Qualcomm co-founder Irwin Jacobs threatened to stop and actually did stop supplying chips to LGE over a licensing dispute that began in 2004. “These chip supply threats are critical for maintaining Qualcomm's unreasonably high royalty rate,” Koh wrote.

Qualcomm said in a statement posted on its website that it will immediately seek a stay of the district court's judgment and an expedited appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. “We strongly disagree with the judge's conclusions, her interpretation of the facts and her application of the law,” said Don Rosenberg, executive vice president and general counsel of Qualcomm.

Federal Trade Commission Competition Director Bruce Hoffman said in a statement on the commission's website that the ruling “is an important win for competition in a key segment of the economy. FTC staff will remain vigilant in pursuing unilateral conduct by technology firms that harms the competitive process.”

The commission's trial team was led by Jennifer Milici and other FTC staff attorneys. Qualcomm has been represented in the FTC matter by a team of lawyers from Cravath, Swaine & Moore; Morgan, Lewis & Bockius; and Keker Van Nest & Peters.

Koh found that licensing represents two-thirds of Qualcomm's value, earning $7.7 billion as recently as 2016. That's more than Ericsson, Nokia, InterDigital and nine other licensors of modem chip patents combined, Koh found.

Qualcomm has maintained dominance over the CDMA and LTE markets through a variety of anticompetitive practices, the judge wrote. Those include “no license, no chips,” which includes the refusal to provide chip samples, technical support or enabling software. At the same time, Qualcomm refuses to provide OEMs lists of Qualcomm's patents or patent claim charts during license negotiations, she wrote. And the company has maintained a constant royalty rate of about 5% over some 20 years, even as its contribution to cellular standards is declining and its royalty rates remain “untested by litigation.”

Koh indicated that, based on the FTC's expert testimony and other corroborating evidence, Qualcomm's FRAND royalty rate should be below 1%.

“These unreasonably high royalty rates raise costs to OEMs, and harm consumers because OEMs pass those costs along to consumers,” she wrote. They also “may dissuade” OEMs from investing in new features, because they know they'll have to pay a percentage of the phone sale price to Qualcomm.

Qualcomm also refuses to license its standard-essential patents to other chipmakers, which Koh found “boxes out rivals.” The practice violates Qualcomm's commitment to standards-setting organizations to license on FRAND terms, and Federal Circuit case law that requires royalties be based on the smallest salable patent practicing unit, she found.

“Qualcomm attempts to eliminate competition in certain markets; eliminates competing standards; deprives rivals of revenues to invest in research and development and acquisitions; forecloses rivals from establishing technical and business relationships with OEMs; prevents rivals from field testing with OEMs, network vendors, and operators; and ensures that Qualcomm retains influence in [standard setting organizations], so that Qualcomm can maintain its time-to-market advantage and its unlawful monopoly,” she wrote. “By so hobbling rivals, Qualcomm's practices 'unfairly tend[] to destroy competition itself.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

White & Case KOs Claims Against Voltage LLC in Solar Companies' Trade Dispute

'A Never-Ending Nightmare': Apple Sued for Alleged Failure to Protect Child Sexual Abuse Survivors

'The Hubris of Big Tech': Apple Hit With California Labor Lawsuit for Alleged Free Speech, Privacy Violations

Trending Stories

- 1NJ Supreme Court Clarifies Affidavit of Merit Requirement for Doctor With Dual Specialties

- 2Whether to Choose State or Federal Court in a Case Involving a Franchise?

- 3Am Law 200 Firms Announce Wave of D.C. Hires in White-Collar, Antitrust, Litigation Practices

- 4K&L Gates Files String of Suits Against Electronics Manufacturer's Competitors, Brightness Misrepresentations

- 5'Better of the Split': District Judge Weighs Circuit Divide in Considering Who Pays Decades-Old Medical Bill

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250