'Mash-Up' of Dr. Seuss and Star Trek Held Fair Use

In Dr. Seuss Enterprises v. ComicMix, the Southern District of California granted summary judgment to defendants, affirming its prior findings that a ComicMix illustrated book combining elements of several Seuss children's books with characters, themes and other features of the popular sci-fi series Star Trek was a non-infringing fair use of the Seuss material from which it had admittedly been “slavishly” copied.

May 24, 2019 at 12:00 PM

8 minute read

The original version of this story was published on New York Law Journal

Robert J. Bernstein and Robert W. Clarida

Robert J. Bernstein and Robert W. Clarida

On March 12, the Southern District of California granted summary judgment to defendants in Dr. Seuss Enterprises v. ComicMix, 16-CV-2779 JLS (BGS) (Slip op.), largely affirming its prior findings that a ComicMix illustrated book combining elements of several Seuss children's books with characters, themes and other features of the popular sci-fi series Star Trek was a non-infringing fair use of the Seuss material from which it had admittedly been “slavishly” copied.

The defendants' successful summary judgment motion was the fourth time they had tried to dispose of the case. The action was brought by Seuss in 2016, alleging both copyright and trademark claims. In response to defendants' initial motion to dismiss, the court made a number of findings in defendants' favor as to fair use in a June 9, 2017 ruling (ECF 38). Because the court found a “near-perfect balancing of the factors,” however, it declined to dismiss the copyright claims at such an early stage of the litigation. After the filing of an amended complaint, defendants again moved to dismiss on fair use grounds, and again the court denied the motion (ECF 51).

Defendants answered the amended complaint in December 2017 and moved yet again to dismiss (ECF 54), this time moving for judgment on the pleadings on the trademark claims under Rule 12(c), and seeking a ruling from the Copyright Office under §411(b)(2) of the Copyright Act, alleging irregularities in the copyright registrations of the Seuss works at issue. This too failed. Discovery ensued, and defendants took their fourth bite at the apple with a summary judgment motion in December 2018.

The Summary Judgment Ruling

As it had done in previous rulings, the court applied the traditional fair use analysis set forth in §107 of the Act, which considers the following non-exclusive factors:

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The court also applied the non-statutory doctrine of “transformative use,” which the Supreme Court introduced into the fair use analysis in its 1994 Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music decision, 510 U.S. 569 (1994) and which has since become the principal inquiry in most fair use determinations. To oversimplify greatly, the transformative use doctrine requires the court to ask

whether the new work merely 'supersede[s] the objects' of the original creation […] or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message; it asks, in other words, whether and to what extent the new work is 'transformative.'” …Because 'the goal of copyright, to promote science and the arts, is generally furthered by the creation of transformative works[,]' the 'more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use.'

Slip op. at 15, quoting Campbell, 510 U.S. at 579.

Campbell was a parody case, and the court in Seuss held consistently that defendants' Seuss/Star Trek mash-up was not a parody, yet the use was nonetheless “highly transformative,” thus mitigating its commercial nature and any potential harm to the market for the original Seuss works. Boldly going where it had not gone before, however, the court rejected plaintiff's argument on summary judgment that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit's 2018 decision in Oracle America v. Google, 886 F.3d 1179 (Fed. Cir. 2018) should alter the court's prior conclusions under the first statutory factor.

In Oracle, the court found that Google's use of Oracle's “Java” software program was not a fair use, when Google made exact copies of 37 Java API codes from the total of 166 API codes in the plaintiff's work. Unlike the Oracle case, the defendants in Seuss did not engage in “wholesale” copying (even though some of the copying was admittedly “slavish”), nor did the defendants' work serve the “same intrinsic purpose” as the Seuss original. While the defendants' book “may be an illustrated book with an uplifting message (something over which plaintiff cannot exercise a monopoly), it is one tailored to fans of Star Trek's original series.” Slip op. at 17.

Therefore, the Oracle decision was not persuasive as to any transformative use issue before the court in Seuss. Further, the Seuss court refused to find any evidence of bad faith on defendants' part simply because they made a fair use determination about their work without seeking advice of counsel. On balance, the court reaffirmed its prior finding that the first factor under 107 weighed in defendants' favor, despite the commercial nature of their work. Slip op. at 18.

Under the second statutory factor, which looks to the nature of plaintiff's work, the parties did not dispute the court's earlier finding that the factor “slightly favors” plaintiff because its work is highly creative, but that work is also “long and widely published.” The court's two-sentence mention of this factor, and the parties' failure even to fight about it, testifies to how slight its impact is on most fair use determinations.

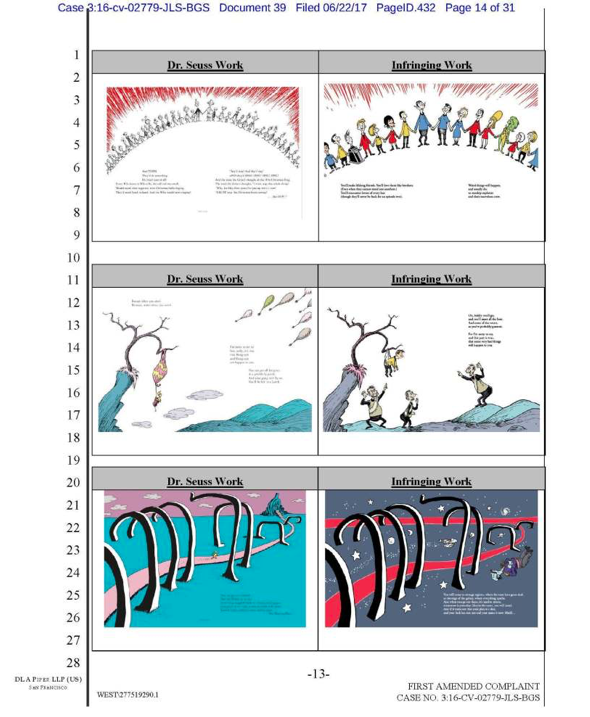

The third factor, which looks to the amount of the copying, was more hotly disputed but still ended up favoring defendants, because the court held that their copying was not more extensive than necessary to accomplish their transformative purpose. The court found that the Seuss case was most usefully compared to Leibovitz v. Paramount Pictures Corp., 137 F.3d 109 (2d Cir. 1998), in which the makers of a Leslie Nielsen Naked Gun movie created a poster and other promotional materials featuring an image very closely modeled after plaintiff's famous photograph of a nude, pregnant Demi Moore that had appeared on the cover of Vanity Fair magazine. The defendants' use in that case was deemed fair. The court in Seuss focused on relatively granular details of the defendants' images to make the point that defendants in that case took even less protectable content from Dr. Seuss than defendants had taken from plaintiff's work in Leibovitz, as in this comparison:

The defendant in Leibovitz incorporated nearly the entirety of the plaintiff's photograph, except for superimposing a different face onto the body [citation omitted] Here, by contrast, defendants took discrete elements of the [Seuss] copyrighted works: cross-hatching, object placements, certain distinctive facial features, lines written in anapestic tetrameter. Yes, these are elements significant to the copyrighted works, but defendants ultimately did not use Dr. Seuss' words, his character, or his universe. The court therefore stands by its prior conclusion that defendants took no more from the copyrighted works than was necessary for defendants' purposes, i.e., a “mash-up” of [Seuss' work] and Star Trek, and that, consequently, this factor does not weigh against defendants.

Slip op. at 22.

Turning to the fourth statutory factor, the Seuss court engaged in extensive analysis of the evidence of Seuss' market for licensed derivative works, but noted that “Plaintiff has introduced no evidence tending to show that it would lose licensing opportunities or revenues as a result of publication of [defendants' work] or similar works.” Slip op. at 30. Ultimately the court thus concluded that “the harm to plaintiff's market remains speculative, and, accordingly, the fourth factor is neutral” Slip op. at 33.

In sum, the court reaffirmed most of its initial conclusions as to fair use and granted summary judgment to defendants on this basis.

Conclusion

In fair use cases, courts will sometimes observe that the parties' works speak for themselves, see, e.g., Brownmark Films v. Comedy Partners, 682 F.3d 687 (7th Cir. 2012) (parties' works are “the only two pieces of evidence needed to decide the question of fair use in this case”). But even when the works may speak for themselves, as they arguably do in Seuss, see ECF 39 (First amended complaint at 13) (reproduced below), there can be sharp disagreement about what they say, and a court may be reluctant to resolve the issue without benefit of a full record. The Seuss court took the latter approach, and it was ultimately the record—in which “plaintiff has failed to introduce evidence tending to demonstrate that the challenged work will substantially harm the market”—that persuaded the court to tip the “near-perfect balancing of the factors” in defendants' favor.

Robert W. Clarida is a partner at Reitler, Kailas & Rosenblatt and the author of the treatise Copyright Law Deskbook (BNA). Robert J. Bernstein practices law in The Law Office of Robert J. Bernstein.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'A Death Sentence for TikTok'?: Litigators and Experts Weigh Impact of Potential Ban on Creators and Data Privacy

Shareholder Democracy? The Chatter Musk’s Tesla Pay Case Is Spurring Between Lawyers and Clients

6 minute read

Many LA County Law Firms Remain Open, Mobilize to Support Affected Employees Amid Historic Firestorm

Trending Stories

- 1'A Death Sentence for TikTok'?: Litigators and Experts Weigh Impact of Potential Ban on Creators and Data Privacy

- 2Bribery Case Against Former Lt. Gov. Brian Benjamin Is Dropped

- 3‘Extremely Disturbing’: AI Firms Face Class Action by ‘Taskers’ Exposed to Traumatic Content

- 4State Appeals Court Revives BraunHagey Lawsuit Alleging $4.2M Unlawful Wire to China

- 5Invoking Trump, AG Bonta Reminds Lawyers of Duties to Noncitizens in Plea Dealing

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250