Picasso Catalog Tests French, US Copyright Laws in Fair Use Judgment

In a win for Sheppard Mullin, U.S. District Judge Edward Davila rules that a judgment obtained by owners of a Pablo Picasso catalog is "repugnant" to U.S. public policy under California's Uniform Foreign Money-Judgments Recognition Act.

September 13, 2019 at 08:25 PM

4 minute read

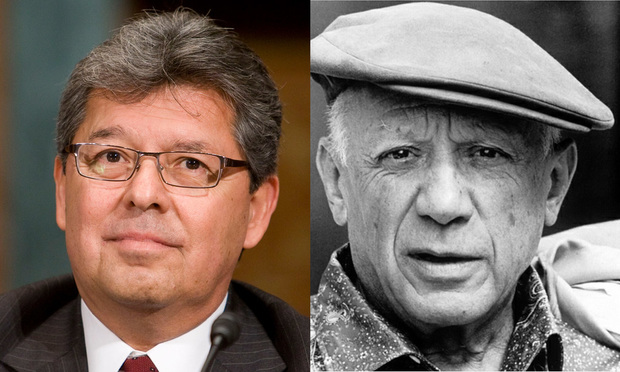

Judge Edward Davila, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California and Spanish painter Pablo Picasso (Photo: Diego Radzinschi/ALM and Wikipedia)

Judge Edward Davila, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California and Spanish painter Pablo Picasso (Photo: Diego Radzinschi/ALM and Wikipedia)Overseas copyright owners are going to have to brush up on U.S. fair use law.

U.S. District Judge Edward Davila on Thursday ruled that a €2 million French judgment could not be enforced against publishers of a Pablo Picasso reference work. Davila ruled that the French judgment is "repugnant" to U.S. public policy, because French law does not have an analog to the fair use defense to copyright infringement.

Davila granted summary judgment to Alan Wofsy and Alan Wofsy & Associates under California's 2007 Uniform Foreign Money-Judgments Recognition Act. Wofsy publishes The Picasso Project, a catalog of some 1,492 photographs of Picasso artwork that originally was published in the Zervos Catalogue.

"While Plaintiffs are correct that the standard for repugnancy is a difficult one to meet, '[f]oreign judgments that impinge on First Amendment rights will be found to be repugnant to public policy,'"Davila wrote in De Fontbrune v. Wofsy, citing a U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit decision that applied New York's version of the Recognition Act.

Sheppard, Mullin, Richter & Hampton partner Neil Popovic, who litigated the case for Wofsy, said that finding was important not only for the result in his case but for the development of the Recognition Act case law. Most states have adopted a version of the law. To the extent courts construe them consistently, it will help provide further guidance in a still nascent area, Popovic said.

Wofsy has been publishing The Picasso Project since 1995. Along with photos, it includes titles, literary references, provenance, current ownership and sales information, much of which is generally not included in the Zervos Catalogue, according to Davila's opinion. The book is a commercial venture whose intended market is libraries, academic institutions, art collectors and auction houses.

Yves Sicre de Fontbrune held the copyright in the Zervos Catalogue, which spans 16,000 photographs of Picasso's works. He sued Wofsy in France in 1996 and got a judgment barring further use of the photos. Violating it would trigger a contingent damage award called an astreint.

De Fontbrune's heirs sued again in 2011 when copies of The Picasso Project were found in a French bookstore. The Wofsy defendants were sued a month before the hearing and did not appear. A French court awarded €2 million. The plaintiffs then sued Wofsy in the Northern District of California to enforce the judgment.

Popovic teaches international law at Berkeley Law and had written an article about enforcement of judgments under the Recognition Act in California. "Some research was done and [the client] called me up," he said.

He knew he would be required to characterize French civil procedure, so he hired DLA Piper partner Vonnick Le Guillou to provide an expert opinion, which Davila cited in his decision.

On fair use, Popovic said the key was explaining the purpose of The Picasso Project. "The publication is a reference work," he said. "It's not designed to compete with the plaintiffs' work in the marketplace."

Davila agreed. "Because The Picasso Project is intended for libraries, academic institutions, art collectors, and auction houses, it falls within the exemplary uses named in the preamble of Section 107 of the Copyright Act," Davila wrote. "This factor weighs strongly in favor of fair use."

Fair use, Popovic said, is an area of law like defamation "where the U.S. departs from the rest of the world. Under our public policy, expression is something to be promoted."

Davila agreed. "The court is mindful of concerns over comity between the French and U.S. courts," he wrote. But French judgment is "at odds to the U.S. public policy promoting criticism, teaching, scholarship, and research. Defendants have carried their burden of showing that there is no genuine issue of material fact that the 2012 Judgment is repugnant to U.S. public policy."

Popovic said the decision should give publishers in California and elsewhere in the U.S. a little more freedom to publish without fear of a foreign judgment, so long as their uses are fair. "Now, if they have assets overseas, that would be a different issue," he added.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Cleary Nabs Public Company Advisory Practice Head From Orrick in San Francisco

Morgan Lewis Shutters Shenzhen Office Less Than Two Years After Launch

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250