How Women Are Rising Up in IP Law

Marilyn Hall Patel, former chief judge of the Northern District of California, and Dechert's Katherine Helm discuss supporting women in intellectual property and finding advocates in unlikely places.

January 24, 2020 at 05:52 PM

9 minute read

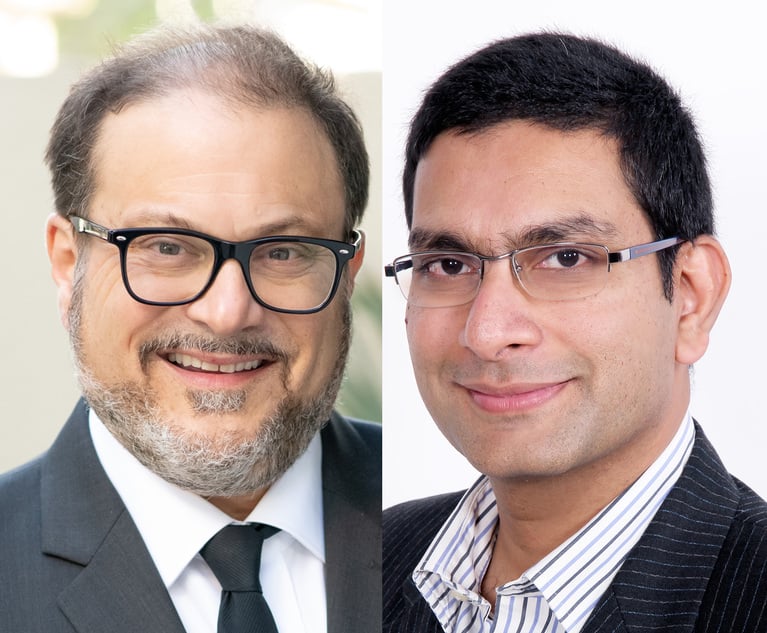

Retired U.S. District Judge Marilyn Hall Patel, left, and Dechert partner Kassie Helm. Left photo: Jason Doiy. Right photo: handout.

Retired U.S. District Judge Marilyn Hall Patel, left, and Dechert partner Kassie Helm. Left photo: Jason Doiy. Right photo: handout.

The Recorder's intellectual property reporter Scott Graham sat down with Marilyn Hall Patel, the former chief judge of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, and her former law clerk Katherine Helm, now an IP life sciences partner at Dechert in New York, to discuss the state of women in IP law. Patel and Helm share when to give young guns a platform, why lawyers should say yes to paternity leave and how U.S. District Judge Jack Coughenour of the Western District of Washington became an advocate for women in the Ninth Circuit.

Answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Kassie Helm: You had the practice in your court, which now has become a little more formalized, you were one of the pioneers of it, of having incentives for more junior lawyers, either women or diverse attorneys, or people who might not get the opportunity …

Marilyn Hall Patel: I never made it one of my local rules, but—it was very funny one time when we were trying a case, the woman on the team—it wasn't a patent case—but I could see she was kicking her senior partner, who wasn't jumping up and doing whatever he should have been doing. And so finally I just said, you know, why don't you let her proceed with it? She seems to know the case pretty well.

Scott Graham: Did they agree?

Patel: Yes, they did. And she did a great job.

Helm: You had a reputation, Judge [William] Alsup also, people knew that he did that.

Graham: Still does, right?

Patel: He actually embodied it in a local rule.

Helm: Now it's become more common, and several district courts have done it. I think it's great. I've used it to inform clients, this is why you should put a junior, a mid-level, let them argue that motion or this smaller thing.

Patel: Sometimes, they're the one that knows the case. And the senior partner comes wheeling in with all the grandeur of that title and has no clue what's going on. There are some clients that are very traditional and want the older senior partner, even though the senior partner doesn't know a thing about the case.

Helm: True. I think it's an education.

Patel: Well, it's an education across the board. Law firms are so afraid of their clients. It's intimidating, when you think you might lose a client because you make a decision that isn't related to the merits of the case.

Helm: Well, I think it's incumbent upon the law firm then to explain why it is related to the merits of the case. The person that you should be supporting to run that litigation, argue that motion, take that deposition is the one that knows it best. And that your informal practice of the person behind passing the Post-it notes to the person in front who might not know all the details—that's happening.

Patel: Who should take the laboring oar here? Does it fall to the court to say, "OK, we've got a new regime here?" It should be everybody. But ultimately, it seems to me the court does have a responsibility to say something.

Helm: I think it's wonderful that the court says something. I think it gives the law firm extra credibility to the client. It's a carrot and not a stick. More minutes and argument.

Patel: Even now, and I'm glad it's working out well for you [Kassie], but I think for a lot of women still, over the general patent field, they are still sort of looked at as second wheels. Is it changing?

Helm: It's changing, but it takes a long time to change. At law firms, the level of attrition for women is very high. And if people don't figure out how to combat that, you're never going to have enough women at the higher ranks that are doing those jobs.

I remember several years ago when I was an associate, not at Dechert, someone was giving us a talk about partnership, and they were touting how X-many women had been in the partnership class that year, which was higher than it had been the year before. And they said we're hoping that there'll be a time when there's gender parity in the partnership class. And then someone else said, you know, if every law firm started making every class of partners 50% women, we would still not see gender parity in the firm partnerships in anyone in this room's lifetime. Just on the numbers, that's how long it's going to take.

Graham: Is [attrition] about family issues or other reasons?

Helm: I certainly think there are many other reasons. One thing that's improving quite rapidly about family issues is that they're becoming non-gender specific. Most of the policies at law firms now, parental leave, anyone can take it, lawyers and nonlawyers. And I think culturally, more and more men are taking them.

Last year I was staffing a litigation, and there was a mid-level associate, a man, who I thought would be great on the case. He had experience in the jurisdiction the case was going to be brought in. And I called him and said, "This is a great client. This is going to be a great matter. I'd really like the chance to work with you. I think you'd be great on this case. I hope you can do it."

And he said, "Thank you so much for thinking of me. I'd be honored and it sounds wonderful. I should let you know, my wife and I are expecting, and I plan on taking the full [three-month] leave. So if that affects your staffing decision I totally understand."

And I kind of paused. And I thought, really, there's only one way to respond here. "No. 1, congratulations. That's absolutely wonderful. That's far and beyond the best news. No.2, of course I'd love to have you on the team. And No. 3, see you in 2020."

It was difficult because I had to staff someone in on the interim. The client had to get to know multiple different people. He had to get caught up to speed and then you're paying for someone else to do all sorts of things. And that's how it is.

Patel: How difficult is it to accommodate those situations if you have two or three people that fall in that same category?

Helm: Well, you just have to do it. It has to become a cultural norm. Because if it's not, then men will not think it's OK to take the parental leave even if it's non-gender specific. Every person who does it makes it OK for the next one.

Graham: One thing that hasn't changed a lot. In the busiest patent districts in the country—between Delaware, the Eastern District of Texas, the Central District of California—there are very few women among the district judges hearing patent cases. The Central District of California patent pilot program, all six of the district judges are men.

Helm: I did have a number of cases in the Central District of California before Judge [Mariana] Pfaelzer, before she passed. And she was known for supporting women. She had several cases where I know that lawyers went out of their way, because they thought it would be helpful in front of the court, to put women on the trial team, either local counsel or leading the team. That was more an instance of informality, it wasn't in her local rules. But that got women some roles in the court. That probably got me some arguments I might not otherwise have had.

Patel: We had judges meetings regularly. One of the issues was always women. In fact, the whole Ninth Circuit did a study of women in the courtroom. It not only dealt with judges or the lack thereof, the litigants, women witnesses, women jurors, you name it. Everything. And what was very clear from all of that was that women were not being recognized for their participation in the same way that men were.

We had a Ninth Circuit conference, I still remember this. I was on a panel. I got [Judge] Jack Coughenour from Seattle to sit on the panel. Because I figured you have to have a man who has that sort of macho credibility. And he was considered a trial lawyers' trial lawyer. He was appalled by [the results of the study]. So he carried the ball for us in the Ninth Circuit in getting some changes for us with respect to women in the courtroom, period. He helped us set up a committee that then tried to address these issues. And he went out to speak all over the country.

And I really felt it would be better to let him do it. Because if it had been me, people would have said, "Well, what do you expect?" Somehow, I had a sense with Jack, the conversations I'd had with him, while he was an old trial lawyers' trial lawyer, [he] was with us. He was a disciple for getting more women on the bench, for treating women differently in the courtroom, all of that. He was really supportive.

Graham: I know that you [Kassie] are working with ChIPs. Are there any particular initiatives that you're working on there?

Helm: ChIPs always has some great initiatives. I'm one of the founders of the New York chapter. ChIPs chapters are expanding almost every day. We're doing our first European summit this spring. We have a Next Gen summit that's annual, where more junior attorneys get opportunities to do mocks, opportunities to get in front of clients, which is great. Particularly in the Bay Area. ChIPs is incredibly strong.

Patel: Well, that's where it started.

Helm: It did start here. We have several ties to SDNY [as well]. Judge [Loretta] Preska has been a huge supporter of ChIPs. We've now hosted two events at SDNY. She's encouraged several of the other female judges at SDNY to attend, and they do, which is great. It gives women in IP more of a presence before the court.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

How I Made Office Managing Partner: 'Stay Focused on Building Strong Relationships,' Says Joseph Yaffe of Skadden

US Patent Innovators Can Look to International Trade Commission Enforcement for Protection, IP Lawyers Say

How the Deal Got Done: Sidley Austin and NWSL Angel City Football Club/Iger

Trending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250