With Californians Needing Access to Justice, the California Bar Should Advance Reform

Diversifying and innovating the profession will result in increased access to justice: more people will get better legal help for less money and more lawyers will practice law in new ways.

May 13, 2020 at 11:00 AM

5 minute read

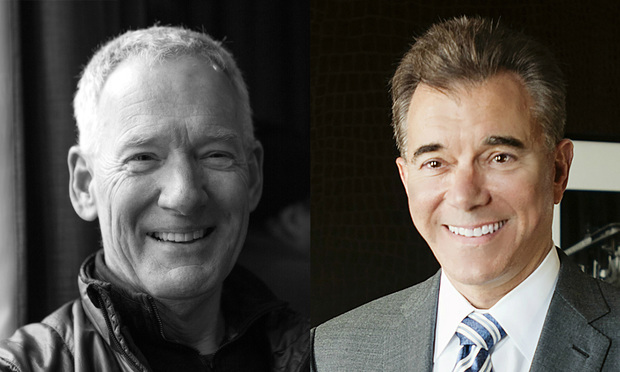

John Lund, Parsons Behle partner and Ralph Baxter former Chairman and CEO of Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe (Photo: Courtesy Photo)

John Lund, Parsons Behle partner and Ralph Baxter former Chairman and CEO of Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe (Photo: Courtesy Photo)

The coronavirus pandemic has laid bare the long-standing dysfunction of the way legal services work in America. The legal needs of ordinary citizens have been dramatically increased by the pandemic and the economic crisis it has caused.

We have long had a genuine crisis in access to justice; in 2019, 70% of Californians facing a legal problem received no legal assistance. Repeated, thoughtful proposals for reform have been quashed by those in the profession who believe they benefit from the status quo.

The pandemic makes the crisis worse. Americans need lawyers now more than ever. But they aren't using them because they can't afford them, can't find them, and, often, don't even know their personal issues have a legal solution.

We are both long-time lawyers and leaders. One of us was president of the bar in a mid-sized state. One of us was chair of a global law firm. The noble calling of the legal profession has guided us all our lives. We know our profession needs to change.

California has an opportunity to lead that change. On Thursday, the State Bar Board of Trustees votes on whether to move forward with reforms to the rules governing the practice of law in California. Their decision will then be reviewed by the California Supreme Court.

We urge the Bar and Court to embrace bold leadership, advancing these reforms that will benefit citizens and small businesses throughout California. The issues are complicated and numerous. There is no simple answer; there rarely is. Here is a fundamental place to start:

Allow Nonlawyers To Participate in the Business Side of Law

California Rule of Professional Conduct 5.4 forbids lawyers from sharing income of a law practice with "nonlawyers," either as partners or investors. This ban has profoundly negative impacts on lawyers and the market for legal service, in several ways. Here are two:

One: It prevents law firms from raising equity capital critical to build and sustain their businesses, forcing them to rely on debt and after-tax income instead. This is not much of an issue for the largest firms. But it is completely debilitating for the firms that advise the majority of individuals and small businesses with their daily legal problems. Imagine how the technology sector would fare without access to private capital to fund research and growth.

Two: It impedes innovation. Law firms are years behind other professions and industry in modernizing how they do things. In addition to not having access to capital, Rule 5.4 prohibits lawyers from sharing income with anyone other than lawyers. New ideas and different perspectives are essential for innovation. Where would technology innovation be if companies could not offer equity to key employees as they grow?

The adverse impact of Rule 5.4 is starkly evident. Without it, lawyers could partner with hospitals and doctors, with accountants and social workers, and with technology companies and in other businesses. Lawyers could practice law with stable salaries and benefits as staff attorneys in consumer-focused law companies, serving more Californians through technology at scale.

Opponents of change argue that modifying Rule 5.4 would harm the public because the interest of nonlawyer owners or investors would cause a "race to the bottom," forcing lawyers to serve clients badly, even fraudulently, to make a profit. The preposterousness of the idea that lawyers are immune from profit motive or that lawyers alone are morally incorruptible should be obvious. Indeed, there is no evidence to support this argument. Jurisdictions that have allowed nonlawyer investment, such as England & Wales and Australia, have seen increased innovation and no decline in the quality of legal service or the amount of work for lawyers. No jurisdiction has reinstated the ban on nonlawyer ownership after repealing it.

Lawyers should be leading the charge for this reform. A noble profession does not exalt its own interests over those of whom it is sworn to serve. Lawyers are leading in Utah and Arizona, where state supreme courts have proposed reforms to permit nonlawyer ownership and investment with careful oversight.

California should be in the vanguard of reform. Diversifying and innovating the profession will result in increased access to justice: More people will get better legal help for less money and more lawyers will practice law in new ways. The proposal before the Board, developed over almost two years of study and following the model already approved by Utah's Supreme Court, outlines a regulatory "sandbox" approach, allowing limited relaxation of Rule 5.4 to permit new business models and services under careful oversight. The Bar's leadership has been heavily pressured by special interest groups of lawyers trying to protect their own interests. The Bar must not allow lawyers' fear and self-interest to undermine the needs of all Californians. Failure to advance regulatory reform would be a moral failure of the public's trust in a time of acute crisis.

The Bar should advance reform by approving the regulatory sandbox and allowing nonlawyer investment and ownership of legal services in California.

Ralph Baxter served as Chairman and CEO of Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP from 1990 to 2013; he is now an advisor to legal technology companies and writes the blog Legal Services Today and co-hosts the podcast Law Technology Now. He has been a member of the California Bar for 45 years. John Lund is a past president of the Utah State Bar, co-chair of the Utah Implementation Task Force on Regulatory Reform, and a partner at the Salt Lake City firm of Parsons Behle.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Cleary Nabs Public Company Advisory Practice Head From Orrick in San Francisco

The Rise of Female Breadwinners: Challenging Traditional Divorce Dynamics

4 minute read

An Overview of Proposed Changes to the Federal Rules of Procedure Relating to the Expansion of Remote Trial Testimony

15 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Settlement Allows Spouses of U.S. Citizens to Reopen Removal Proceedings

- 2CFPB Resolves Flurry of Enforcement Actions in Biden's Final Week

- 3Judge Orders SoCal Edison to Preserve Evidence Relating to Los Angeles Wildfires

- 4Legal Community Luminaries Honored at New York State Bar Association’s Annual Meeting

- 5The Week in Data Jan. 21: A Look at Legal Industry Trends by the Numbers

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250