Law School Grad: California Bar Exam Decision Is a 'Hurtful Half-Measure'

"Let's be clear, the court and the California Bar have set us up for failure," says Shandyn Pierce, a 2020 graduate of the University of California Hastings College of the Law.

July 22, 2020 at 07:30 PM

7 minute read

Shandyn H. Pierce is a 2020 graduate of UC Hastings College of the Law and a proud Legal Education Opportunity Program alum. (Courtesy Photo)

Shandyn H. Pierce is a 2020 graduate of UC Hastings College of the Law and a proud Legal Education Opportunity Program alum. (Courtesy Photo)

Last Thursday, the California Supreme Court rendered its final decision regarding the fall 2020 bar exam. The court moved the exam to Oct. 5-6, permanently lowered the cut score, and directed the bar to implement a provisional licensing program, which would allow 2020 graduates limited practice in specified areas under supervision of a licensed attorney.

David Faigman, dean and chancellor of UC Hastings College of the Law, praised the decision:

"The decision was rather more than I thought I could hope for, and certainly more than I expected. I am deeply grateful to the California Supreme Court for this decision, which takes into account the needs of the candidates for the bar and ensures protection for the public."

I'm not sure what it is we are celebrating.

Ultimately, the Class of 2020 is faced with a Hobson's choice: We will take the October exam, or we will take nothing at all. Let's be clear, the court and the California Bar have set us up for failure.

On one hand, we are offered a test whose validity, under the best of circumstances, is questionable. Now, under the stress of a once-in-a-century plague, a great social uprising, shifting deadlines and timelines, familial responsibilities, and financial strain, we must face an unproven exam. An exam which will not be scored or scaled by the National Committee of Bar Examiners, as have tests in years past. An exam whose results will not be available until the middle of January, rendering those who fail helpless to prepare for a February administration. An exam which will seemingly require 10,000 or so of us to "voluntarily" surrender our sensitive biometric data. An exam which will still require applicants to have a reliable internet connection, and a dedicated, quiet place to sit and engage in intense focus for hours on end. Not to mention the as-yet unanswered question of how the Bar will effectively ensure unscrupulous applicants will not cheat.

Of course, there is also the very real question of whether the California Bar can pull off an online administration this October. Last week the American Board of Surgery (ABOS) attempted to administer its certification test online. This two-day exam is made up of over 300 questions on a variety of surgery topics. The stakes are high because passing the exam is required for medical residents to make the final transition into board-certified surgeons. More than 1,000 applicants sat for the online exam, and the ABOS made use of a proctoring system which required a number of security measures, including facial recognition scans.

The administration was a dismal failure. The testing system failed, and the ABOS was forced to cancel the entire examination after the first day. The ABOS has also launched an investigation into the proctoring system due to security and privacy concerns. Worse, over 1,000 medical residents, who spent weeks studying under historically difficult conditions, are now left in limbo. Some will not have the time to ramp up for another exam because they need to work to provide for themselves and their families.

The October bar exam has roughly 10 times as many applicants as the ABOS exam. It will be administered online. And the California Bar has proposed the use of similar proctoring methods. The similarities are plain. The danger is plain. Yet, the court and the bar have engaged in a stunning suspension of disbelief, and ask 2020 applicants to do the same.

On the other hand, we have the "choice" to accept and utilize a provisional license. A basic grasp of reason and common sense reveals that this is a false choice. The next exam is in October. If provisional licensees skip this administration, they will likely be looking for a February offering, which raises several problems.

First—the Bar's magical thinking aside—we don't know if there will be a February administration. Second, how will applicants, who face a very real need for financial assistance and stability, be able to self-select out of a job that provides that stability, to sit for a future exam? Even if licensees start work this month, they will likely have to ask for leave in three to four months' time. Or, worse, they will attempt to study for the bar while working to support themselves or their loved ones. Others will have to consign themselves to the fact that they will be unable to sit for the bar until July 2021. At which point, they will likely be even more reliant upon their jobs and the need for financial stability. An interpretation of the court's letter which would allow applicants to retain their provisional license until they pass "a" bar exam provides no cure—the provisional license path walks 2020 graduates to the gateway of a vicious cycle.

Simply put, this "choice" is a sham. This October administration is a sham. The court's letter exhibits not the well-reasoned decision that was promised, but the hubris of the bar and the legal elite. The court's strong encouragement that law schools use their facilities to assist graduates who are taking the exam is a salient example. The state of California currently has more coronavirus cases than the entire United Kingdom. Moreover, the Cal State and UC systems have both formally announced plans for online instruction in the fall. And Gov. Gavin Newsom's recent order evinces that K-12 schools in at least 30 counties, including San Francisco County, where the court sits, will not be open in the fall. What reasonable interpretation of this data would lead the court to conclude that California law schools will have the ability to provide the accommodations suggested?

Finally, much praise has been heaped on the court regarding its decision to lower the bar exam cut score. Why? This decision was long overdue. There are long-standing questions regarding the exam's ability to determine minimum competence. Additionally, as the American Civil Liberties Union recently pointed out to the court, racial disparities in bar passage rates persist. There is no denying the documented, historical exclusion of people of color from the California Bar.

Moreover, the court's action is not praiseworthy, because this sudden flip showcases the faulty reasoning which underlie its previous arguments in opposition to lowering the cut score. And it reveals the action for what it truly is: A naked attempt to placate the Class of 2020, other industry members and observers.

Ultimately, the court has engaged in a hurtful half-measure. Hurtful, because it took so long to decide. Hurtful, because it exhibited a pernicious, if not willful, ignorance as to the lived-in reality of applicants.

I, like many 2020 graduates, will be sitting for the October bar exam. I, like many of my peers, read the court's letter and realized the truth: Nothing has changed.

Shandyn H. Pierce is a 2020 graduate of UC Hastings College of the Law and a proud Legal Education Opportunity Program alum. At Hastings, Pierce consistently engaged in community advocacy and mentorship while serving as president of Hastings' Black Law Student Association and as subregional director of the National Black Law Student Association.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

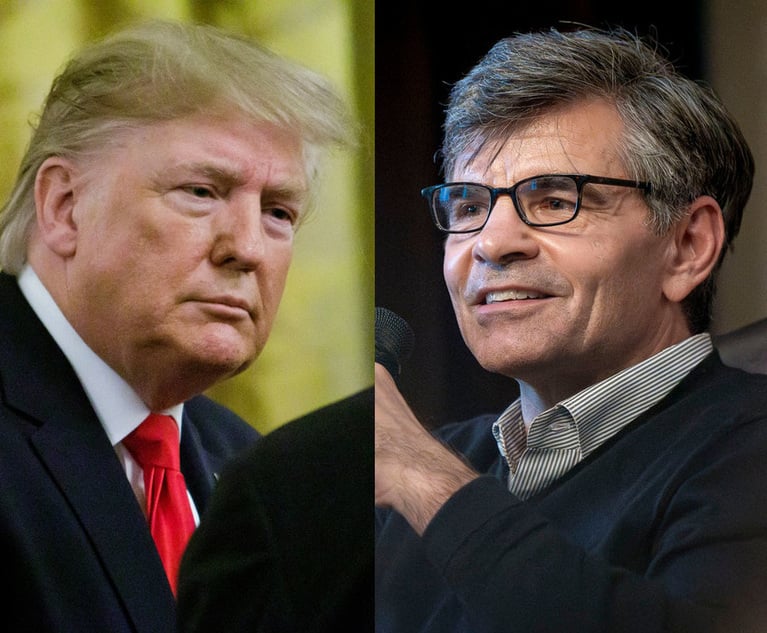

ABC's $16M Settlement With Trump Sets Bad Precedent in Uncertain Times

8 minute read

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250