Shareholder Activism in a COVID-19 World: Past, Present and Future

"All it takes is a single activist to have a more optimistic view than the market and a belief that their ideas will help to close a perceived gap between price and value," write Sidley Austin's Derek Zaba and Kai Liekefett. "With this backdrop, general counsel and their legal teams would be wise to consider how prepared they are for activism in a COVID-19 world."

July 30, 2020 at 01:54 PM

6 minute read

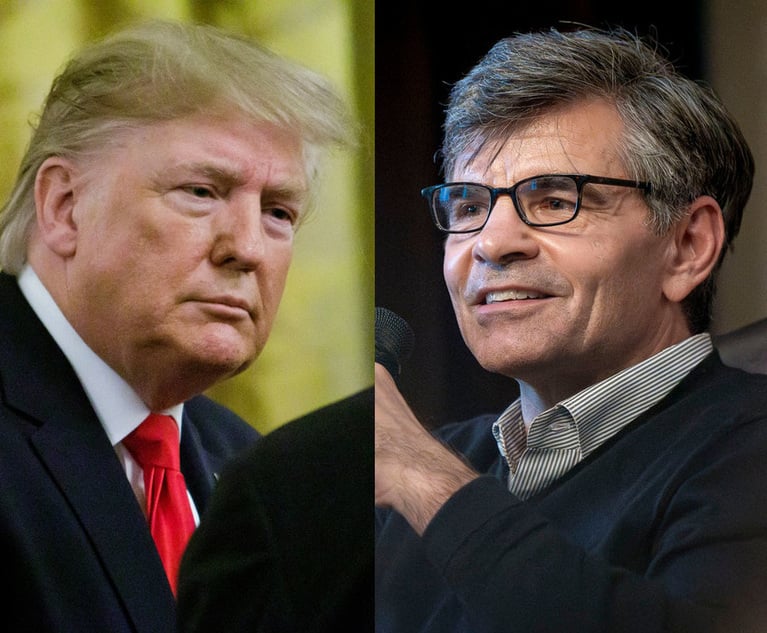

Derek Zaba and Kai H.E. Liekefett, partners in Sidley Austin's Palo Alto and New York offices. (Courtesy photo)

Derek Zaba and Kai H.E. Liekefett, partners in Sidley Austin's Palo Alto and New York offices. (Courtesy photo)

As the COVID-19 pandemic began to unfold in early March, it quickly became clear that the crisis would act as a "poison pill" that would sharply reduce shareholder activism in the spring. Initially, many activists were preoccupied with their own survival and/or attracting new capital rather than launching new campaigns. Additionally, it became difficult to obtain shareholder support for public activist campaigns at a time when boards and management teams were focused on managing through the immediate crisis.

In addition, conditions were ripe for a surge in adoptions of poison pills, formally known as shareholder rights plans. For many companies, responding to stock prices that had collapsed 50% or more in a matter of days was a component of managing through the crisis. At the same time, equity trading volumes had increased and thus an activist or potential hostile acquirer was able to accumulate a large stock position quickly. Additionally, the increased volatility and general upheaval in the equity markets resulted in atypical trading patterns (and other behaviors), diminishing the effectiveness of traditional stock watch methods to identify activist accumulations that rely on pattern recognition.

In the first few weeks of the crisis, more than a dozen pills were adopted. Shortly thereafter, proxy adviser firms Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis both published guidance indicating greater acceptance of short-duration poison pills in the current circumstances. For example, ISS's April 8 guidance specifically noted that "[a] severe stock price decline as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to be considered valid justification in most cases for adopting a [one-year] pill." As a result, approximately 50 companies adopted "poison pills" by mid-May. To further put this number in perspective, only 25 S&P 1500 companies had a poison pill in place at the end of 2019, according to FactSet.

However, as the equity markets have bounced back and volatility has subsided, both issuers and shareholder activists are transitioning to the next phase in the rapidly evolving shareholder activism landscape. Management teams have removed their firefighter gear and begun to consider the longer-term implications of the COVID-19 crisis. This is evident in the trends of poison pill adoptions: in June and July, fewer than 10 poison pills in total have been adopted, which is a far cry from the pace of adoptions in prior months.

Likewise, activists have begun to look past the summer and are preparing for the fall and winter. Many have or are building positions and are reaching out to the companies that are next on their current hit list. After being forced to the sidelines during proxy season, many activists are anxious to prosecute campaigns. Companies with director nomination deadlines in the early fall or whose governing documents permit shareholders to call a special meeting or act by written consent are particularly vulnerable in the current environment. It is also not necessarily the case that strong stock price performance protects you. Certain industries, such as many in the technology sector whose businesses are largely insulated from the most deleterious effects of a continued COVID-19 crisis, offer safe(r) haven to investors, including activists. Many of these industries also happen to be those where customer behavior and industry dynamics have been most disrupted by the COVID-19 crisis, resulting in an increased possibility of a divergence between the current stock price and an individual investor's assessment of intrinsic value. All it takes is a single activist to have a more optimistic view than the market and a belief that their ideas will help to close a perceived gap between price and value.

With this backdrop, general counsel and their legal teams would be wise to consider how prepared they are for activism in a COVID-19 world. In doing so, they should ask themselves the following questions:

- Understand the attractiveness to an activist of your business in the current environment. Has your stock price been disproportionately impacted versus your business? Has your stock performed reasonably well but the crisis changed the strategic appeal of the company to a potential suitor?

- Understand your governance vulnerabilities. Beyond understanding your business, strategic and financial vulnerabilities, what are possible attacks on your board, compensation, ESG and other governance issues? Has an activist law firm reviewed these issues from a proxy fight perspective?

- Develop an activism response plan and assemble a team. If an activist publishes a 100-page white paper or calls your CEO's private phone number to announce their presence, what are your initial steps? How quickly can you assemble your key internal constituents and external advisors to respond appropriately?

- Have an up-to-date shareholder rights plan "on the shelf." This entails conducting the proper diligence and drafting the necessary documentation to ensure that a poison pill could be adopted immediately upon the identification of a threat. If there is another swoon in the equity markets, are you prepared to implement a rights plan overnight if warranted?

- Review your bylaws and other governing documents. Are your bylaws and other governing documents up to date with constantly evolving activist tactics?

Derek Zaba and Kai H.E. Liekefett are partners in Sidley Austin's Palo Alto and New York offices, respectively, and co-chairs of the firm's shareholder activism practice. Zaba and Liekefett devote 100% of their time to shareholder activism defense and proxy contests. Combined, they have defended more than 70 proxy contests in the past five years. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected].

This article has been prepared for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. This information is not intended to create, and the receipt of it does not constitute, a lawyer-client relationship. Readers should not act upon this without seeking advice from professional advisers. The content therein does not reflect the views of the firm.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

ABC's $16M Settlement With Trump Sets Bad Precedent in Uncertain Times

8 minute read

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250