Michael Avenatti's Latest 5th Pleas Lead to Unusual Debate Over Deposition Admissibility

"That's one thing you're not going to see in any case law," said attorney Chris Wesierski, who represents Avenatti's former clients William Parrish and Timothy Fitzgibbons.

May 09, 2022 at 11:12 AM

8 minute read

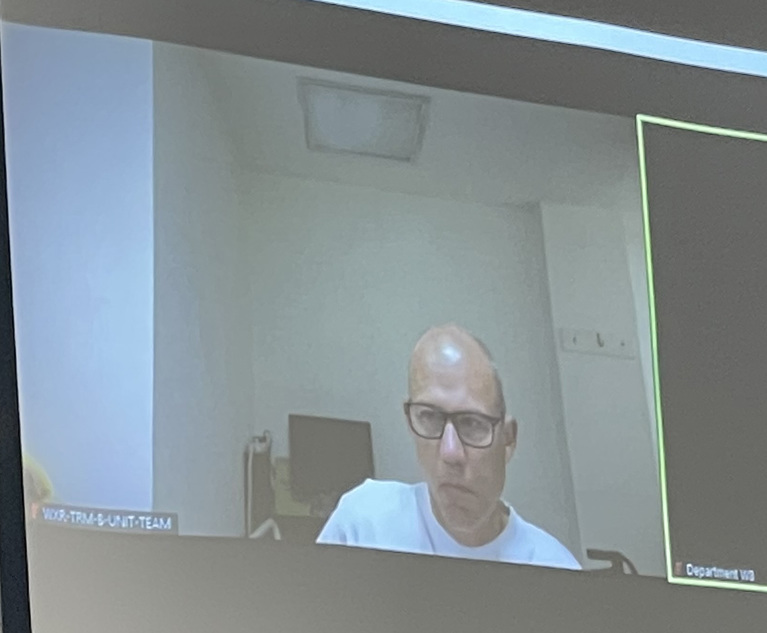

Federal inmate Michael Avenatti appears via video in Orange County Superior Court Judge Walter Schwarm's courtroom at the West Justice Center in Westminster, California, on April 13, 2022. Photo: Meghann M. Cuniff/ALM

Federal inmate Michael Avenatti appears via video in Orange County Superior Court Judge Walter Schwarm's courtroom at the West Justice Center in Westminster, California, on April 13, 2022. Photo: Meghann M. Cuniff/ALM

A California state judge preparing for trial in an attorney-fee dispute is considering an unusual legal issue regarding depositions: Should one from seven years ago be played for jurors if the witness now refuses to say whether the testimony was truthful? What if the witness was a lawyer, who at the time represented the men now being sued based in part on that testimony?

The attorneys trying to keep the deposition away from a jury are arguing that the would-be witness' recent invocation of his right against self-incrimination deprives them of their right to cross-examination.

They also say everyone has ample reason to distrust every word of it: It's from Michael Avenatti, the suspended and imprisoned lawyer who's awaiting sentencing in the Southern District of New York and a retrial in the Central District of California while already serving a 30-month sentence, all for crimes involving clients.

They want to question Avenatti in trial, but a judge recently ruled that he can invoke his right against self-incrimination under California Evidence Code 940—California's version of the Fifth Amendment—for essentially all substantive questions.

The attorneys say Avenatti's refusal to even attest to the truthfulness of the 2015 testimony shows that he's apparently worried about possible perjury charges related to it. Coupled with what they contend is a lack of opportunity to cross-exam, they say the legal issue moves far beyond a typical admissibility question regarding depositions, which are frequently used in trials to impeach live testimony or when a witness isn't available.

"If the jury is told this is sworn testimony under oath from Avenatti, we cannot defend that. We cannot attack that because of his invocation of self-incrimination rights," Chris Wesierski, who represents Avenatti's former clients William Parrish and Timothy Fitzgibbons with attorney Larry Conlan of Cappello & Noël in Santa Barbara, told Orange County Superior Court Judge Walter Schwarm last week. "That's one thing you're not going to see in any case law."

'Don't Worry'

Through Wesierski and Conlan, Parrish and Fitzgibbons are fighting accusations that they aided and abetted Avenatti's theft of Los Angeles lawyer Robert Stoll's $5.4 million attorney fee from a $39 million settlement Avenatti secured in 2011 with noted plaintiffs lawyer Brian Panish.

One of their trial witnesses is Edith Matthai, a veteran Los Angeles legal ethics lawyer who was enlisted to testify about Avenatti's fee-sharing agreement.

Avenatti initiated the case in June 2011, seeking an order that he didn't owe Stoll anything following an unsuccessful mediation with JAMS co-founder Jack Trotter. He participated in the 2015 deposition while representing Parrish and Fitzgibbons with Robert Baker of Baker, Keener & Nahra of Los Angeles at his side as his counsel. Parrish and Fitzgibbons now accuse Avenatti of duping them into unnecessary litigation, and their new lawyers say they have proof Avenatti promised them Stoll's money was being kept in a client-trust account until the dispute resolved.

"Mr. Avenatti lied to them, said, 'Yes, I have it in a trust account. Don't worry, I will defend you if he sues you,'" Wesierski said in court last week. "As soon as Mr. Avenatti got the money in his account, he spent it on his own house, on his own personal watches, whatever he was going to buy."

Representing Stoll, H. James Keathley of Keathley & Keathley in Irvine, said Avenatti's deposition is admissible because Avenatti was rightfully sworn to tell the truth.

The fact that Parrish and Fitzgibbons now believe Avenatti didn't properly represent them is an issue for a malpractice claim or a bar complaint, Keathley said, but it shouldn't affect the admissibility of Avenatti's deposition.

"Avenatti testified that he was directed and instructed who not to pay and how much not to pay," Keathley said, which "is consistent with what the evidence is going to show."

Fair Chance at Cross-Exam?

Calling into court Thursday from federal prison, Avenatti told Schwarm that Parrish and Fitzgibbons were represented in his deposition by both him and Baker, which means they had ample opportunity to cross-examine him then. Any suggestion otherwise is "ludicrous and absurd" and also "sanctionable," Avenatti said.

Avenatti also implied the issue isn't complicated, telling Schwarm, "Frankly, if I'd been hit by a bus six months ago, I don't think there'd be any question Mr. Keathley could utilize the deposition testimony. But I'll leave that decision for your honor."

However, Parrish and Fitzgibbons, who didn't attend the deposition, say they didn't know Avenatti was blaming them for the fee dispute with Stoll until years later.

"The only person that could have cross-examined Michael Avenatti was Michael Avenatti, and he was the one being deposed," Wesierski told Schwarm. "He was our clients' attorney, so there was no reason for our clients to cross-examine him at the time of the deposition, and no reason for him to cross-examine himself."

Avenatti's deposition is the only direct evidence tying them to any wrongdoing, Wesierski said, and Avenatti gave it after he knew that he'd been caught stealing the money so he was "dumping it on his own clients. Which is unheard of."

Keathley said he has other evidence to establish Parrish and Fitzgibbons' involvement, including client accounting documentation and evidence of two meetings between only Parrish and Stoll in which Parrish told Stoll that he wouldn't be paid. He described Parrish and Fitzgibbons as "two extremely bright men" who "knew they were going to get sued," and said that the argument that Avenatti's deposition is unfairly prejudicial is not legally valid.

"If all evidence was made inadmissible for being adversely prejudicial to one side or the other, you would have no evidence at all," Keathley said.

5th Pleas Complicate

The unusual debate follows Schwarm concluding on May 2 that Avenatti could possibly incriminate himself if he testifies in the trial, so he's allowed to refuse to answer questions under Evidence Code 940. The judge also reiterated a 2019 ruling that defaulted Avenatti out of the case for not participating.

Avenatti represented himself in the multiday hearing in Schwarm's courtroom at the West Justice Center, via video and telephone from Terminal Island federal prison near Long Beach. He had much more to say when not under oath, including telling Schwarm that Parrish and Fitzgibbons "are not victims, and they never will be victims."

Conlan wants to "make me out to be the bad guy," Avenatti said, despite Avenatti securing Parrish and Fitzgibbons a $39 million settlement.

"Mr. Conlan's entire defense has been nothing but a series of personal attacks on me, and I'm tired of it," Avenatti said.

Conlan responded, "I didn't make Michael Avenatti the bad guy in this case. Michael Avenatti made Michael Avenatti the bad guy in this case."

"It's my job to make sure the truth comes out, and that Mr. Parrish and Mr. Fitzgibbons are not wrongfully blamed for something they did not do. That is my strategy," Conlan continued.

The lawyers are due back in Schwarm's courtroom Monday at 10 a.m., with jury selection possibly beginning Wednesday or Thursday. The judge said last week that he's "got to work through this Fifth Amendment issue and the depositions."

"I want to take a little bit of time with that," Schwarm said.

The judge also is considering whether to allow Wesierski and Conlan to separately present Avenatti's criminal convictions as evidence, though he questioned Thursday whether it's necessary when neither side is disputing Avenatti mishandled Stoll's money; rather, the key issue is Parrish and Fitzgibbons' involvement.

Avenatti is no longer participating in the case now that Schwarm has confirmed he defaulted. He's been in custody since surrendering Feb. 7 in Santa Ana following a New York federal jury convicting him Feb. 4 of wire fraud and aggravated identity theft for defrauding former client Stormy Daniels of $148,750 in book contract money.

He's not currently expected to be called as a witness given his intended Fifth pleas, but Avenatti said last week that he'll be unavailable for four to six weeks as he travels to Manhattan and back for sentencing in the Daniels case before U.S. District Judge Jesse Furman in the Southern District of New York.

On Friday, Senior U.S. District Judge James Selna in the Central District of California ordered California prosecutors to inquire about the feasibility of Avenatti being sentenced via video, though Furman has already declined Avenatti's request for a remote appearance.

Selna scheduled Avenatti's California retrial for July 5 and scheduled a May 16 hearing in which a U.S. Marshals Service representative is to explain the transport system.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Morrison & Foerster Doles Out Year-End and Special Bonuses, Raises Base Compensation for Associates

Microsoft's Banner Year Pushed Brad Smith's Pay Sharply Higher

Big Tech to Big Law: Is the Compensation Gap Closing?

Gibson Dunn Breaks $3B Revenue Mark With Litigation, Transactions Firing on All Cylinders

Trending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250