'He's a Liar': Orange County Jury Blames Michael Avenatti for $5.4M Attorney Fee Dispute, Clears Ex-Clients

A judge on Monday is to consider a default judgment against Avenatti, who initiated the case in 2011 but eventually stopped responding to filings.

June 23, 2022 at 07:15 PM

6 minute read

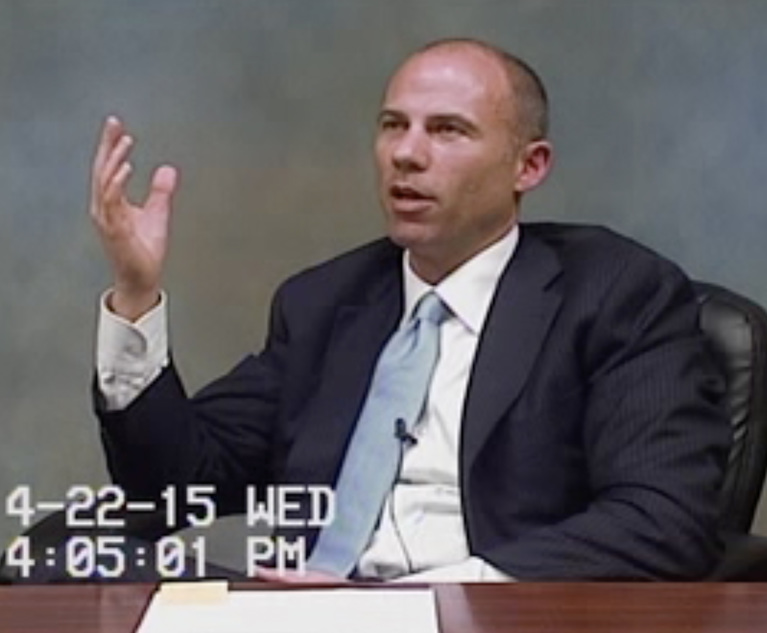

Michael Avenatti sits for a video deposition in 2015 in a civil dispute with a former co-counsel. The deposition was that was evidence in an Orange County Superior Court trial that ended with a defense verdict on June 22, 2022. (Courtesy photo)

Michael Avenatti sits for a video deposition in 2015 in a civil dispute with a former co-counsel. The deposition was that was evidence in an Orange County Superior Court trial that ended with a defense verdict on June 22, 2022. (Courtesy photo)

With his three federal criminal cases nearly over, Michael Avenatti still managed to garner another judicial blemish this week in the form of a jury verdict delivered in a lawsuit over a former co-counsel's missing $5.4 million attorney fee.

It was unanimous, even though it didn't have to be: After about 2 1/2 hours of deliberation on Wednesday for an 18-page verdict form, all 12 Orange County Superior Court jurors agreed Avenatti "substantially" interfered in Los Angeles attorney Robert Stoll's ability to collect money he was rightfully owed.

The jury concluded Stoll hadn't done his fair share of the work, but they still concluded he was due something. They wouldn't, however, blame the people Stoll wanted to blame: his former clients William Parrish and E. Timothy Fitzgibbons.

Instead, jurors said afterward that they felt as though Avenatti was on trial, and they convicted him of everything they could. A few discussed their verdict with the attorneys in the hallway outside the courtroom, saying they feel bad for Stoll and believe he's owed money, also while calling Avenatti a liar and a sociopath who victimized his own clients by dragging them into a lawsuit that's dragged on for 11 years.

"We all agree he's very smart. He's calculating. He's charismatic. He knows how to disarm people," the jury forewoman said.

Left to right: Chris Wesierski, William Parrish, Larry Conlan and E. Timothy Fitzgibbons. (Photo: Meghann M. Cuniff/ALM)

Left to right: Chris Wesierski, William Parrish, Larry Conlan and E. Timothy Fitzgibbons. (Photo: Meghann M. Cuniff/ALM) The 2015 video deposition that gave jurors a firsthand look at the now-imprisoned Avenatti contained "a couple of tells" that indicated deceit, she said, including awkwardly long pauses and repeated hand scratching when discussing Parrish and Fitzgibbons' roles, which their new lawyers pointed out in trial.

"He's a liar. They are victims," the forewoman told a reporter.

Though Avenatti initiated the case in 2011, seeking an order that he didn't owe Stoll anything, he eventually stopped responding to filings and wasn't allowed to participate in the trial as a party. Instead, Orange County Superior Court Judge Walter Schwarm is scheduled to enter a default judgment against him on Monday, money Stoll and his lawyer James Keathley don't expect they'll ever see.

After the verdict was read Wednesday, Stoll told Parrish and Fitzgibbons' lawyers Chris Wesierski of Wesierski & Zurek and Larry Conlan of Cappello & Noël that he holds no ill will against them. Parrish also told Keathley he was a great lawyer who did well with the evidence he had.

The trial featured six days of testimony, including from Brian Panish of Panish Shea Boyle Ravipudi in Los Angeles, who was co-counsel with Avenatti and Stoll on the case and testified last about his own financial disagreement with Avenatti.

As laid out in trial testimony and exhibits, it was Panish who first joined forces with Stoll to represent Fitzgibbons and Panish in a malicious prosecution lawsuit against their former company FLIR Systems, which had unsuccessfully sued them for trade secrets misappropriation.

Panish brought in Avenatti, and they ended up securing a $39 million settlement from FLIR in 2011, with about $15.4 million in attorney fees. Parrish and Fitzgibbons fired Stoll but testified they trusted Avenatti was keeping Stoll's portion of the attorney fees in a client trust fund as he worked through their payment dispute. Each testified they didn't know until after they fired Avenatti in 2018 that he'd blamed them for the dispute.

With Stoll's firm Stoll, Nussbaum & Polakov as the plaintiff, Keathley accused Parrish and Fitzgibbons of breach of contract, vicarious liability, conversion and aiding and abetting Avenatti's conversion and breach of fiduciary duty, with Avenatti's 2015 deposition as key evidence. In his closing, Keathley also pointed to testimony from Panish in which Panish said he told Avenatti him to work things out with Stoll, but Avenatti told him the clients didn't want to.

Nationally renowned trial lawyer Brian Panish leaves Orange County Superior Court's West Justice Center in Westminster, California, on Monday, June 13, 2022. Photo: Meghann M. Cuniff/ALM.

Nationally renowned trial lawyer Brian Panish leaves Orange County Superior Court's West Justice Center in Westminster, California, on Monday, June 13, 2022. Photo: Meghann M. Cuniff/ALM. "This shows right there that it's the client that are controlling the distribution of the attorney fees. Not Mr. Avenatti or his firm," Keathley said. He also noted that Stoll's firm advanced $5,300 in costs while Panish advanced $4,700, but Panish got paid more than $5 million while Stoll was left empty-handed.

Keathley also tried to counter Wesierski and Conan's assertion that Panish's reputation as a winning trial lawyer payed a role in the settlement, noting that Panish and Avenatti sued Latham & Watkins over its representation of FIIR but lost, and Parrish and Fitzgibbons had to pay Latham's $1.6 million in attorney fees.

"Which shows right there they weren't afraid of Mr. Panish or his reputation," Keathley said.

Conlan had a simple explanation for what happened, telling jurors in his closing that Parrish and Fitzgibbons "were represented by an attorney that's just a bad guy."

"He's a liar. he's a convicted felon. You cannot trust him as a witness," Conlan said of Avenatti. Avenatti was also determined never to pay Stoll, probably first because he truly didn't believe he deserved anything, then later because Avenatti knew the money was gone.

Conlan also pointed out a couple points in Avenatti's 2015 deposition that jurors referenced in their comments afterward, including two occasions in which Avenatti said he distributed the attorney fees at the direction "of counsel" only to be corrected by his own attorney, Robert Baker of Baker, Keener & Nahra in Los Angeles.

"Directed pursuant to the client. You said 'counsel,'" Baker, who's off camera, can be heard saying.

"Yes, client," Avenatti corrected himself.

"When you think about whether you can trust Michael Avenatti—whether he really corroborated Mr. Stoll's story—you've got to think about that testimony and whether it looks to you like he's telling the truth," Conlan told jurors.

Conlan also referenced testimony from forensic accountant Barbara Luna, who detailed how Avenatti spent the attorney fees he told Parrish and Fitzgibbons he was keeping in a trust account.

"What motive do the clients have to all Michael Avenatti get them dragged into a lawsuit so he can spend the money on a house, clothes and donations to his law school that only benefit him? There is no motive," Conlan said.

Conlan and Wesierski wanted to call Avenatti as a witness, but the judge allowed him to invoke his Fifth Amendment right against self incrimination after a multi-day hearing.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

The Ethics of Freelance Lawyering, Part 4: Fee-Splitting and Malpractice Insurance

6 minute read

The Ethics of Freelance Lawyering, Part 1: Duty to Inform the Client and Fees Charged to the Client/Upcharging

6 minute read

Lewis Brisbois Sues Realty Firm Cushman & Wakefield Over $86K+ in Unpaid Legal Fees

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher Sues to Enforce $1 Million Judgment Against Ex-Client

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250