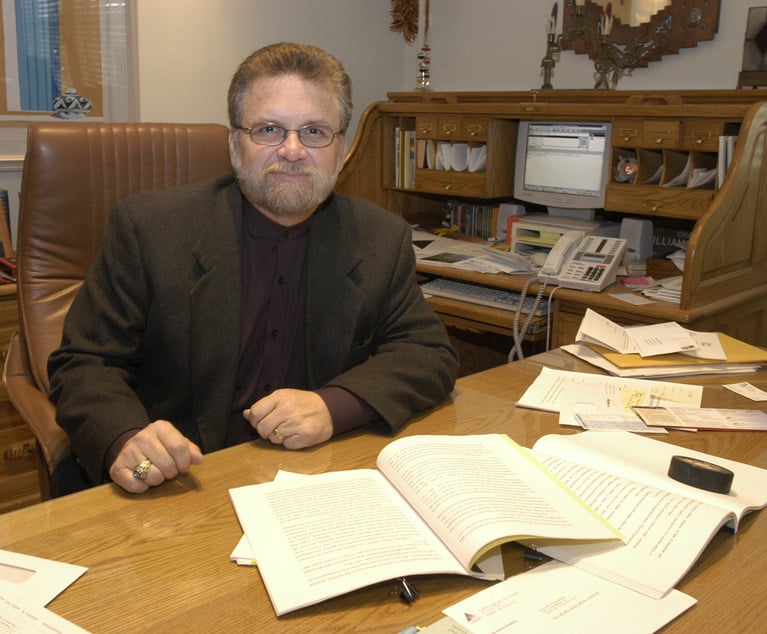

Justice William Bedsworth, California Court of Appeals for the Fourth District

Justice William Bedsworth, California Court of Appeals for the Fourth District Bedsworth: Finding Authoritative Authorities

"It's fine to cite the great philosophers—like Justice Gilbert and I do—but you have to be a lot more careful with your case citations. Older case citations are always greeted with suspicion," says Justice William Bedsworth.

May 25, 2023 at 04:19 PM

7 minute read

My friend Art Gilbert recently penned a decision for the Second District Court of Appeal that begins with this sentence: "The Greek philosopher Heraclitus observed that 'nothing endures but change.' The California legislature must have had Heraclitus in mind when it changed a variety of laws in the penal and juvenile codes."

Heraclitus.

Talk about "well-established authority." Heraclitus wrote about 2,500 years ago. He is famous for saying, "No man ever steps into the same river twice," so apparently swimming had not yet been invented when he was holding forth.

Heraclitus mused long and hard on the idea the world is always in flux, always changing, and this impermanence has imponderable repercussions for philosophical thought. Imponderables we need to ponder. That's apparently what he took from the experience

Art Gilbert can get away with citing Heraclitus because Art understands Heraclitus. Art knew Heraclitus. Art's the last surviving member of Heraclitus' fishing club.

If you aren't familiar with Justice Gilbert, the dean of the California appellate courts, you should take immediate steps to fill that gap in your experience. Art's not only conversant with ancient Greek philosophers,1 he's a first-rate legal mind, he writes a column for the Daily Journal, plays a professional-level jazz piano, and is the nicest, most affable member of the California Court of Appeal.2

The Second District Court of Appeal, Division 6, in Ventura, named their courtroom after him. You go to argue in that court, you walk under a sign welcoming you to the "Arthur Gilbert Courtroom."3 That beats the hell out of, "Abandon all hope, ye who enter here." Kudos to Division 6.

The rest of us aren't Art Gilbert, so we don't have impressive Greek friends to quote. I, for example, have pretty much limited my study of great Greek stuff to gyros. I would be hard-pressed to distinguish Democritus or Demosthenes from Spanakopita or Souvlaki.

Not that I lack culture. In People v. Bennett, (1998) 68 Cal. App. 4th 396, 398, I quoted the great Kentucky philosopher Patty Loveless, observing that, "The trouble with the truth is it's always the same ol' thing."4

Granted, in most judgments, Art's citation would be given credit for more erudition than mine, but then how many hit records did Heraclitus have? Huh? How many?

Art runs a little deeper than me. But at least none of the guys I went fishing with in the eastern Sierra drowned in the river.5

It's fine to cite the great philosophers—like Justice Gilbert and I do—but you have to be a lot more careful with your case citations. Older case citations are always greeted with suspicion. You cite a case that predates Bruce Springsteen or Meryl Streep, you'd better be ready for skepticism. You might as well walk into a playground in a trench coat.

And if you're practicing criminal law, you have to be even more current. In criminal practice, any case older than the bananas in your kitchen is suspect.

When I was in the District Attorney's Office,6 my friend Dennis LaBarbera held our record for the oldest case citation ever used in a brief. People v. Indian Peter, 1874, California Supreme Court. Volume 48.7

He never heard the end of it. Judges began referring to him as "Indian Peter." "I had Indian Peter in my court today; he did a good job." He eventually left the county, and I often wondered if that was part of his decision.

Another thing you want to be careful with is unpublished federal decisions. This is a pit you may not have realized was even available for you to fall into. It's a fluke.

With exceptions only worth discussing if your law review editor says your article is too short, California unpublished decisions can't be cited at all. And out-of-state unpublished decisions get you nowhere. As was said in America Online v. Superior Court, (2001) Cal. App. 4th 1, 6, fn.2:

"Both here and in the trial court, the parties cite unpublished out-of-state decisions. [Former] Rule 977 of the California Rules of Court prohibits citation to our state's unpublished opinions, thus we are hardly inclined to consider those of the Massachusetts Superior Court, federal district courts in Illinois and New York, or Florida trial courts and Court of Appeal."

But unpublished federal opinions are citable. "Unpublished federal opinions are citable notwithstanding [Rule 8.1115] which only bars citation of unpublished California opinions." Haligowski v. Superior Court, (2011) 200 Cal.App.4th 983, 990, fn.4.8

Don't ask me why. Ask Art Gilbert. See what Heraclitus says about it.

All I know is that your unpublished federal authority is citable. Whether it will do you a lot of good is another matter.

We had an unpublished decision from a federal district judge cited to us recently. We read it. It was well-considered and well-expressed. But it was the decision of one judge. It had not been reviewed by anyone.

So, of course, what happens is that we read it, and if we agree with it, we think, "Good for him/her. He/she got it right." Which is just another way of saying, "Good for him/her. He/she agrees with me."

Essentially, it's like an amicus curiae brief from someone with no ax to grind. And that's not nothing. But neither is it the Philosopher's Stone.

What you're telling me is that a federal judge I know nothing about came to this conclusion.

That's interesting. I'll want to read what he/she has to say.

But my job involves a lot of disagreeing with smart trial judges. Some of them probably feel like it's all I do. The fact this judge's thoughts showed up in a book doesn't make them gospel.

If I sat down to lunch with Cormac Carney or Fred Slaughter9 and said, "By the way, I have this issue before me; what do you think about it,"10 I'd be interested in—and grateful for—their opinion. But the fact Cormac or Fred disagrees with me isn't gonna move the needle a lot.11

I'm not required to follow a federal judge's opinion. And if Fred and Cormac couldn't change my mind, it's unlikely the opinion of someone I've never met—and whose legal chops I know nothing about—is going to get much more traction than the trial judge.

Heck, I've got six other justices, people whose expertise and judgment I know and trust, trying—desperately—to keep me from leaving the roadway. They'll attest to how difficult that task can be. But having a bystander on a bus bench waving a map at me isn't likely to help much.

So yeah, you can cite an unpublished federal decision, and if it's more eloquent than you are, it might do you some good. Otherwise, consider Heraclitus or Patty Loveless.

1. As noted above, some of them literally so.

2. A tougher competition than you might imagine.

3. My research turned up no support for the canard that they named it after him because he negotiated the deal with Pio Pico for the land it sits on.

4. "The Trouble with the Truth," written by Gary Nicholson (Sony Cross Keys Publishing Co. Inc. 1991) Four Sons Music (ASCAP).

5. Alright, I've beaten that joke to death. I'll stop.

6. Insert your own "When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth" joke here.

7. Be careful handling that volume; unless you have an airtight law library filled with argon gas, it tends to be a little crumbly.

8. Nothing to say here. Just couldn't resist the opportunity to footnote a footnote.

9. The list of federal judges who might be lured into sitting down to lunch with me is somewhat limited.

10. Which, by the way, I'm not allowed to do.

11. Although it might serve to reassure them.

William W. Bedsworth is an associate justice of the California Court of Appeal. He writes this column to get it out of his system. A Criminal Waste of Space won Best Column in California in 2018 from the California Newspaper Publishers Association (CNPA). And look for his latest book, "Lawyers, Gubs, and Monkeys," through Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and Vandeplas Publishing. He can be contacted at [email protected].

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

US Courts Announce Closures in Observance of Jimmy Carter National Mourning Day

2 minute read

'Appropriate Relief'?: Google Offers Remedy Concessions in DOJ Antitrust Fight

4 minute read

Federal Judge Named in Lawsuit Over Underage Drinking Party at His California Home

2 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1'It's Not Going to Be Pretty': PayPal, Capital One Face Novel Class Actions Over 'Poaching' Commissions Owed Influencers

- 211th Circuit Rejects Trump's Emergency Request as DOJ Prepares to Release Special Counsel's Final Report

- 3Supreme Court Takes Up Challenge to ACA Task Force

- 4'Tragedy of Unspeakable Proportions:' Could Edison, DWP, Face Lawsuits Over LA Wildfires?

- 5Meta Pulls Plug on DEI Programs

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250