RICO Claims by Foreigners

A 2016 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court closed the door on civil Rico claims by foreign plaintiffs suffering injuries abroad. International Litigation columnists Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky examine cases in which the lower courts have scrambled to sort out what may be left of foreign-based civil RICO claims.

February 15, 2018 at 02:40 PM

11 minute read

The Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), 18 U.S.C. 1961 et seq., has, over the past few decades, become a potent weapon for plaintiffs, particularly for those seeking redress for financial and other frauds. The act owes much of its potency to its affording treble damages plus attorney fees for those injured by it. But a 2016 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court closed the door on civil Rico claims by foreign plaintiffs suffering injuries abroad. This article looks at cases in which the lower courts have scrambled to sort out what may be left of foreign-based civil RICO claims.

'RJR Nabisco'

As the Supreme Court said in its 2016 decision in RJR Nabisco v. the European Community, 136 S. Ct. 2090, 2096 (June 30, 2016), “RICO is founded on the concept of racketeering activity,” which RICO defines as any one of a long list of state and federal criminal statutes, including mail fraud and wire fraud. RICO imposes criminal responsibility on those who engage in a “pattern” of racketeering violations in connection with the operation of an “enterprise.” RICO also permits private plaintiffs who have been “injured” through a violation of RICO to bring civil suits. As the statute states:

Any person injured in his business or property by reason of a violation of section 1962 of this chapter may sue therefor in any appropriate United States Court and shall recover threefold the damages he sustains and the cost of the suit including a reasonable attorney's fee … .” 18 USC 1964 (c). (emphasis added).

In Nabisco, the Supreme Court addressed a decision of the Second Circuit in which it had held that RICO does not require, in a civil case such as the one before it, a domestic injury if there was a foreign injury that was caused by a violation of a predicate statute that applies extraterritorially. 764 F. 3d 149, 151 (2d Cir. 2014). The Supreme Court disagreed, distinguishing between criminal violations of RICO, which are concerned with conduct, and civil claims, which the court said “raise issues beyond the mere consideration whether underlying conduct should be allowed or not.” 136 S. Ct 2106. The court thus applied a stricter test to civil claims because providing a private civil remedy for foreign conduct creates a potential for international friction” with “significant foreign policy implications.” Id. (referring to and quoting from Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co., 133 S. Ct. at 1665). Thus, “It is not enough to say that a private right of action must reach abroad because the underlying law governs conduct in foreign countries. Something more is needed,” and, in the case at hand, it was absent. 136 S. Ct. 2108.

In summary, the Supreme Court set out a new rule for private rights of action under RICO: “Section 1964(c) requires a civil RICO plaintiff to allege and prove a domestic injury to business or property and does not allow recovery for foreign injuries.” 136 S. Ct. 2111. The court did not further describe what constitutes an “domestic injury to business or property” other than to observe: “The application of this rule in any given case will not always be self-evident, as disputes may arise as to whether a particular alleged injury is 'foreign' or 'domestic.'” Id. In Nabisco, since the plaintiffs stipulated that their injuries were foreign and not domestic, the Supreme Court did not need to discuss the nature of the alleged injuries. The lower courts have been left with the task of determining what factual contacts give rise to a “domestic” injury sufficient to support a civil RICO claim.

District courts and, in one instance, the Second Circuit, have since examined the domestic or international connections between the facts in the cases before them and the operative injuries to “business or property” under §1964(c). The courts' analyses have tended to look at injuries from two points of view: the objective—where the plaintiff parted with his money or other property –or the subjective—where the injury was experienced (“felt” or “suffered”). The former category has shown itself to be more readily applicable to injuries to property than to businesses. But, as the Supreme Court predicted, the facts in particular cases play an important role

'Bascunan' and Subsequent Cases

One of the earlier cases dealing with the injury question after Nabisco was Bascunan v. Yarur, No. 15-cv-2009 (GBD) (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 28, 2016). There, the court described the injuries suffered by a Chilean plaintiff through complex frauds with many connections to New York, as an “economic injuries,” which required the court to ask “two common-sense questions: '[1] who becomes poor and [2] where did they become poorer.'” Id., p. 4 of 8. The place where the “economic impact of the injury was ultimately felt” is, the district court said, normally the state of the plaintiff's residence. Based on this analysis and on the fact that the plaintiff resided abroad, the court dismissed the complaint. Thus, the court focused on where the injury was felt, not where it occurred or came into being.

Another frequently discussed case is Tatung Company v. Shi Tze Hsu, 217 F. Supp. 3d 1138 (C.D. Cal. 2016), where the district court declined to follow Bascunan, expressing its concern that “the Bascunan rule amounts to immunity for U.S. corporations who, acting entirely in the United States, violate civil RICO at the expense of foreign corporations doing business in this country.” Id. at 1155. Tatung was a foreign corporation doing business in the United States and had obtained a California court's confirmation of a California arbitral award but was frustrated in enforcing it because of an alleged RICO conspiracy involving fraudulent transfers out of the judgment debtor that had the aim of thwarting its rights in California. Id. at 1156. The court stated, “It would be absurd to find that such activity did not result in a domestic injury to plaintiff [Tatung]” Id. The district court concluded that Tatung had, quoting from Nabisco, “suffered a domestic injury to business or property” for the purposes of RICO's private right of action when it experienced an injury to its U.S. judgment. Id. at 1157.

A few weeks thereafter, a judge in the Southern District of New York, in Almaty v. Ablyazov, 226 F. Supp. 3d 272, 284 (S.D.N.Y. 2016), addressed the decisions in Bascunan and Tatung. The court said that it shared “the Tatung court's hesitation to broadly endorse an absolutist version of the rule that would, for example, categorically preclude foreign corporations with business operations or property interests maintained in the U.S. from bringing RICO actions to recover for injuries to those assets.” Id. at 284. Nevertheless, observing that the Bascunan rule of economic injury is consistent with the Supreme Court's focus in assessing the extraterritoriality of §1964(c) on injuries suffered overseas, it ruled that, although the misappropriations took place in the United States, the plaintiffs “got poorer” in Kazakhstan and that therefore the plaintiffs had failed to allege an “injury suffered in the United States in the U.S.” Id. at 285.

In its ruling, the Almaty court distinguished the facts in the case before it from those in Akishev v. Kapustin, CA No.13-7152, 2016, W.L.7165714 at *68 (D.N.J. Dec. 8, 2016), where the court found there to have been a domestic injury because foreign-based plaintiffs “traveled” by way of the Internet into the defendants' U.S.-based website to send funds by wire transfer to defendant's U.S. bank. The court in Akishev stated: “A person responsible for a United Sates-based fraudulent scheme to defraud people overseas should not escape liability under a federal law that permits private causes of action to redress that fraud simply because the scheme targets foreign citizens over the internet.” Id. at *5-*8.

A later decision by a district court, Armada (Singapore) v. Amcol International, No. 13C 3455 (N.D. Ill. March 21, 2017), recognized the objective-subjective dichotomy, saying that there was an issue as to whether “the relevant questions for purposes of RICO's domestic injury requirement is the location of the business or property injured” or where the injury is suffered. Id. at p. 2 of 4. Although the district court ruled that the injury in the case before it, defendant's alleged interference with plaintiff's attempts to collect on a debt in the United States, was not domestic, it nonetheless certified for interlocutory appeal (not yet decided) “the question concerning the proper understanding of RICO's domestic injury requirement.” Id. at p. 3 of 4.

Another case, Cevdet Aksut v. Cavusoglu, 245 F. Supp. 650 (D.N.J. March 28, 2017) also referred to the two separate lines of reasoning that had emerged in court opinions following the Supreme Court's decision—(1) where the injury was suffered and (2) where the conduct occurred that caused the injury. Id. at 655. Although the court concluded that “the only relevant inquiry is where the plaintiff's injury occurred—i.e., where the impact of plaintiff's injury was felt …” it went on apply a test used by a Southern District court in Elsevier v. Grossmann, 199 F. Supp. 3d 768, 786 (S.D.N.Y Aug. 4, 2016), which it described as being that “property injuries occur where plaintiffs parted with their property or where property was damaged, “ruling that a bill of lading reciting “FOB Izmir” meant that the plaintiff had relinquished control of its property in Turkey rather than in the United States, resulting in a non-domestic injury.

The Bascunan decision was appealed to the Second Circuit, which reversed in part the district court's dismissal of the complaint. Bascunan v. Elsaca, No. 16-3626-cv (2d Cir. Oct. 30, 2017). In doing so, it rejected the district court's analysis based on economic loss as “not helpful,” stating: “All civil RICO injuries are … economic losses of one kind or another.” Id. at p. 8 of 16. Instead, the Second Circuit adopted an objective approach, saying courts should “separately analyze each injury to determine whether any of injuries alleged are domestic.”

In determining whether an injury is domestic, the circuit court said that a defendant's use of the U.S. financial system to conceal or effectuate a tort does not, on its own, turn an otherwise foreign injury into a domestic one,” but an injury to tangible property can be domestic “if the property is physically located in the United States.” Id. The Second Circuit examined each of the plaintiff's claims and found that certain of them gave rise to domestic injuries. One was the stealing of the plaintiff's funds from a trust account in New York. It was, as the court said, “the misappropriation of tangible property located within the United States” and therefore a domestic injury. Id., p. 16. Another was the theft of shares from a New York safety deposit box, which constituted a misappropriation of tangible property. The court said that, since the “principal justification for the domestic injury requirement” of the Supreme Court was the need to avoid “international friction,” that justification did not apply to domestically located property, which foreign persons would expect to be protected by American state and federal law. Id. Thus, the location of the property stolen was the “dispositive factor.” Following this reasoning, the court upheld the district court's dismissal of the remaining claims because they did not involve the taking of property in the United States, only the downstream use of U.S. banks to launder stolen money.

In the only reported decision after Bascunan, the district court, in a new ruling in the Elsevier case, applied its previously articulated rule of relinquishment of control, holding that, in the light of additionally produced evidence, the plaintiff had, in fact, relinquished control of its property pursuant to a fraud in the United States and had therefore experienced a domestic RICO injury. Elsevier v. Grossmann, No. 12 Civ. 5121 (KPF) (S.D.N.Y. Nov. 2, 2017), The court observed, referring to the Second Circuit's opinion, “Even if Elsevier were a foreign entity, this harm would suffice to constitute a domestic injury for RICO purposes.” Id. at p. 5 of 6.

Conclusion

The rule that emerges from the Second Circuit's opinion in Bascunan, leaves open to what extent there may be cognizable domestic RICO injuries to businesses as well as to property, because business losses are arguably more likely to be experienced at the residence of the plaintiff and therefore not domestic. There remains, however, the concern underlying some of the cases that there ought not to be an interpretation of the statute that permits U.S.-based fraudsters to prey on foreigners without consequences under civil RICO.

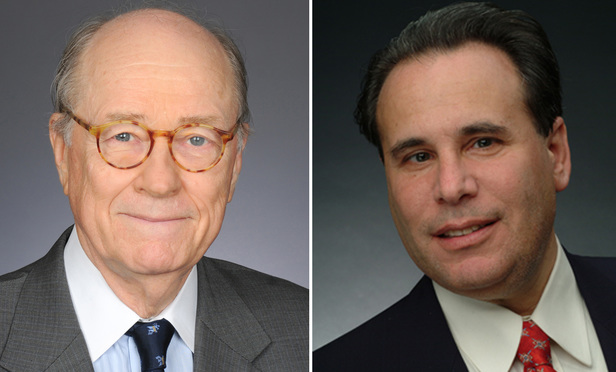

Lawrence W. Newman is of counsel and David Zaslowsky is a partner in the New York office of Baker McKenzie. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected], respectively.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

‘Second’ Time’s a Charm? The Second Circuit Reaffirms the Contours of the Special Interest Beneficiary Standing Rule

Attorney Fee Reimbursement for Non-Party Subpoena Recipients Under CPLR 3122(d)

6 minute read

Here’s Looking at You, Starwood: A Piercing the Corporate Veil Story?

7 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250